Fort Hunter & Queen Anne's Chapel

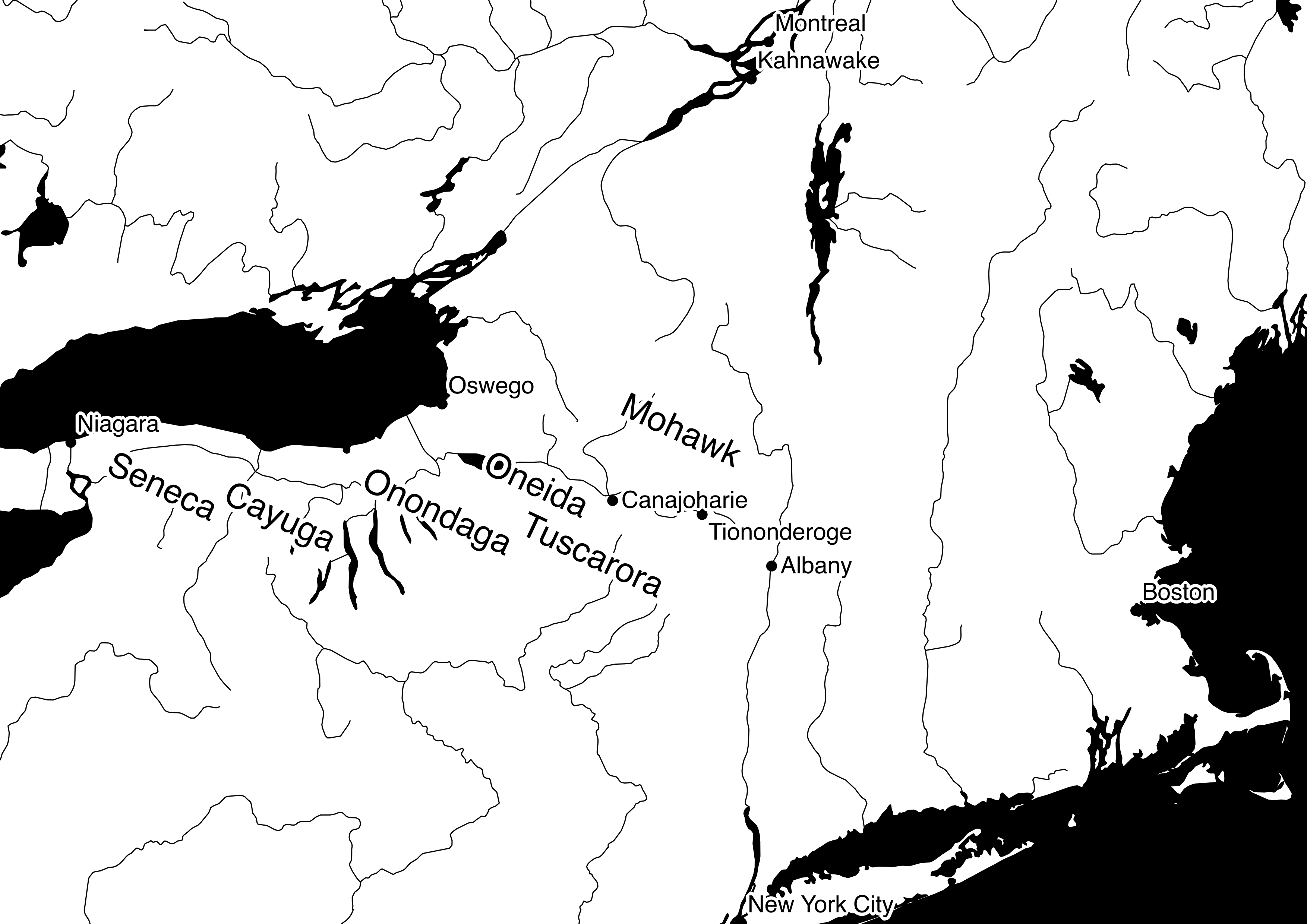

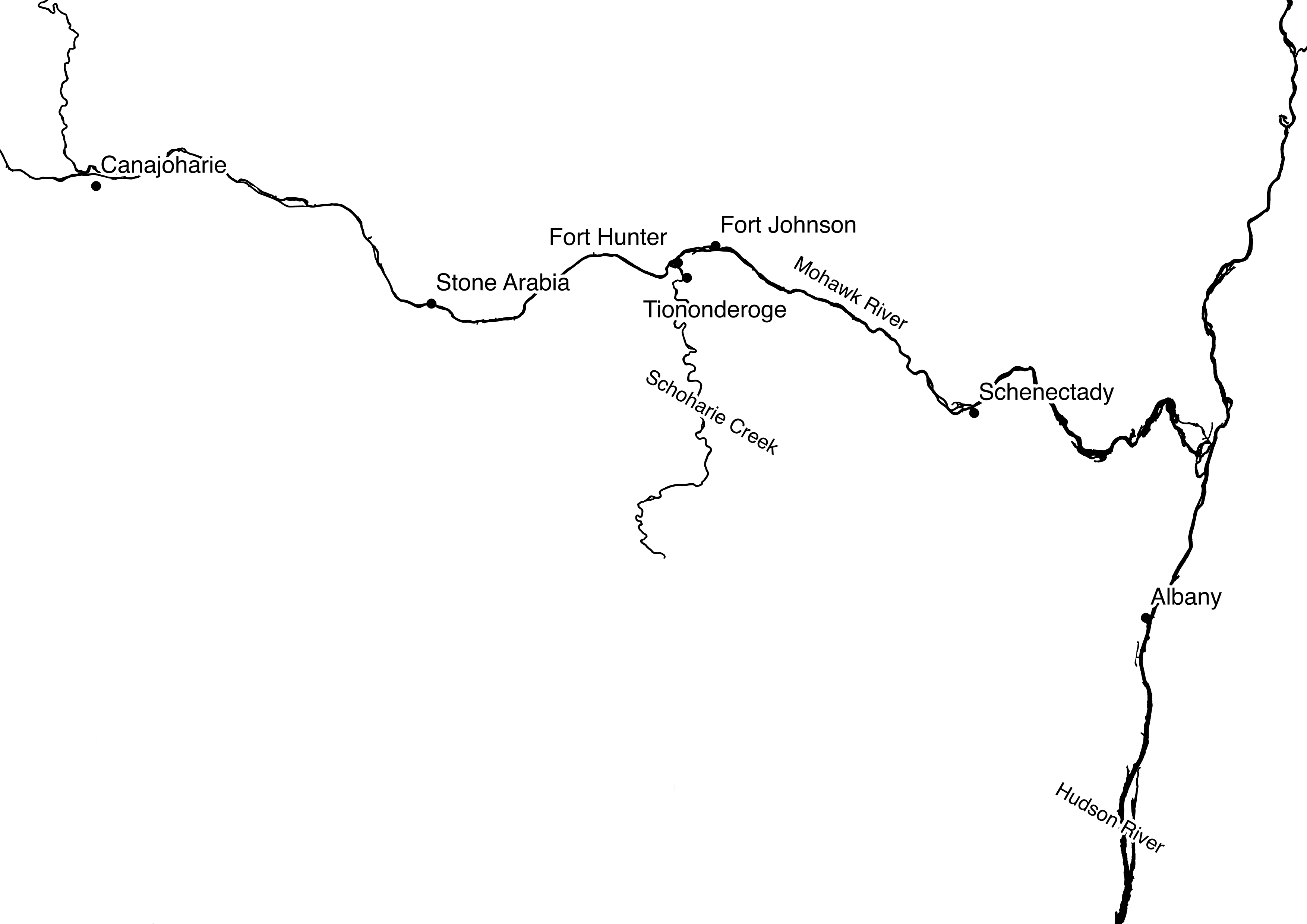

The 1711 construction of Queen Anne’s Chapel in Fort Hunter was intended to serve many goals for the Iroquois and New York colonial leaders who requested it, the British metropolitan officials who funded it, and the Iroquois and settler congregants who attended it. Peter Schuyler, mayor of Albany, and the "Four Indian Kings" (actually three young Mohawks and a Mahican without real authority) traveled to London in 1710 to more firmly tie British imperial interests to the defense of New York and Native communities against French incursion.On the Four Indian Kings’ lack of authority and the way the envoy entered the British imperial imagination, see Hinderaker, "The ‘Four Indian Kings’"; Richter, The Ordeal of the Longhouse, 229-230 and 368n29. full note Queen Anne funded the construction of a fort and a chapel within its walls, hoping to build on previously spotty Dutch and Anglican conversion efforts among the Mohawk and prevent further Catholic conversions by French Jesuits.On previous Dutch and English mission efforts in the Mohawk Valley, see Midwinter, "The Society for the Propagation of the Gospel"; Hart, "Mohawk Schoolmasters and Catechists"; Hart, "For the Good of Our Souls", 213-34; Fenton, The Great Law and the Longhouse, 248-60, 364, 367; Richter, "‘Some of Them'"; Mandell, "‘Turned Their Minds to Religion’"; Strong, "A Vision of an Anglican Imperialism"; Sivertsen, Turtles, Wolves, and Bears, 125. On previous Catholic missions to the Mohawk, see Hart, "For the Good of Our Souls", 36; Fenton, 248-60, 364, 367; Axtell, The Invasion Within, 43-126; Greer, Mohawk Saint. full note For the Anglican Mohawks at Tiononderoge and the nearby Dutch, English, Scots, Irish and Palatine German settlers and enslaved Africans who attended service and baptized their children at Queen Anne’s Chapel, the spiritual community both bound their entangled communities together and reinforced ethnic and racial distinctions within this mixed congregation.

After the construction of the chapel, services were held sporadically by ministers based in Schenectady and Albany, who recorded equally sporadic baptisms and marriages.On Indian conversion in North America, see Hankins; Woolverton, 103; Greer, "Conversion and Identity"; Simmons; Axtell, "Were Indian Conversions Bona Fide"; Cohen; Morrison; Fisher, "Native Americans, Conversion, and Christian Practice"; Salisbury, "Embracing Ambiguity"; Andrews; Fisher, The Indian Great Awakening.full note Henry Barclay, the son of one of these ministers, was appointed by the Society for the Propagation of the Gospel as Catechist to Fort Hunter in 1735 and began keeping a regular "Register of Baptisms, Marriages, Communicants and Funerals at Fort Hunter" recording the names of children baptized, their parents, godparents, witnesses and sponsors.Henry Barclay, Register of Baptisms; Sivertsen, 125; Hopkins, 27; Lydekker, 53-54. On early Anglican practices of register keeping, see Spragge. full note The practice of godparentage, baptismal sponsorship, and baptismal witnessing documented fictive kinship ties between natal families which sometimes, but not often, crossed ethnic and racial lines.On the practice of godparentage and baptismal sponsorship broadly in the early modern period, see Holifield, 53–55; Mintz and Wolf; Bennett; and Smith, "Child-Naming Practices," 13; Wolf, 293-294; Smith, "Child-Naming Patterns," 76; Clark and Gould; Goetz; Tebbenhoff; Spangler; Coster; Lindmark. full note For example, in early 1734 when William and Mary Sixbury presented their child Cornelius for baptism, Cornelius was sponsored by John Hough and Mary Phillips. Later that same year, when William Sixbury and John and Susan Bowen sponsored the infant son of William and Cornelia Bowen, the adults reinforced natal ties between brothers John and William Bowen, ties across natal families between their wives, and ties of friendship or more distant relation with William Sixbury.

The communities surrounding Fort Hunter which attended service and baptized their children at Queen Anne’s Chapel were mixed and varied, and practiced baptism and sponsorship in different ways. The Mohawk community of Tiononderoge, where most of the Iroquois Fort Hunter congregants lived, had a long history of mixed material culture in which European goods were used and reworked to fit indigenous contexts, as well as a hybrid practice of Christianity which blended indigenous, Catholic, and Protestant elements.On Mohawk material culture, see Moody and Fisher, 8; MacLeitch, 175-210; Preston, 178-215; Jordan, 264 and 342. See also the purchases of Fort Hunter Mohawks in Fonda, "Account Book," 1768-1775 and Fonda, "Indian Book" Mixed material culture among the Oneida and Tuscarora is discussed in Preston, 287; Glatthaar and Martin, Forgotten Allies, 239-262; Wonderly, 19-42. On hybrid Mohawk spiritual practice, see Richter "Some of Them" and Mandell, "Turned Their Minds to Religion." full note As a result of a long-disputed land purchase, Dutch and English residents of Albany settled near Fort Hunter and brought enslaved Africans with them.Sivertsen 42-47; Rink; and Cohn full note In addition to these groups, in 1710 New York governor Robert Hunter sponsored the settlement of thousands of Palatine German refugees in the pine barrens of the Mohawk and Hudson Valleys in a scheme to make naval stores for the Royal Navy and provide refuge for Protestants displaced by war in Europe.Roeber, 12-16 and 21-24; Matson, 257-258; Leder, 16-54; Kammen, 177-179; Sivertsen, 72-74; Otterness, 92-96, 99-102, 119-125, 128-131; DRCHNY, 5:460; MacLeitch, 93-94. full note When the pitch scheme turned sour, delegations of Palatines established friendly relations with Schoharie Valley Mohawks and settled instead on fertile farmland along Schoharie Creek, angering Dutch and English elites in Albany and Governor Hunter, all of whom had begun speculating on the land along Schoharie Creek despite Mohawk objections.Paxton, Joseph Brant and His World, 12-13. full note By 1753, the Palatines and Schoharie Valley Mohawks petitioned the New York governor together to make an allowance for the Palatines to remain on the land they had settled, "for we are on[e] church and we will not part. We are grown up together and we intend to live our lifetime together as Brothers."Petition of Hendrick, Abraham Peterson and others to George Clinton, 8 February 1753; SWJP, 1:368; Sivertsen 159-160; Otterness, 115-117, 120-122; MacLeitch, 135-136, 147-151, 166-172. full note After 1718, Ulster Scots and Protestant Irish filtered into the area as well, including William Johnson, who arrived in 1738 to administer land his uncle had bought in the area.Kammen, 178-179; Ford, The Scotch-Irish in America, 249-259; O’Toole, White Savage, 37; Bonomi, Factious People, chapters 1 and 2 passim. full note In addition, some Mahicans moved into the area seeking agricultural work with European landowners or as indentured servants.On the impact of colonialism, debt, and indentured servitude among northeastern Algonquian groups, see Grumet, The Munsee Indians; Otto, The Dutch-Munsee Encounter in America; Mandell, Behind the Frontier; Silverman, "The Impact of Indentured Servitude on the Society," 622. full note

All One People

In this mixed landscape, people from two Native nations with very different relations to settler communities, European ethnic groups at odds with one another, and enslaved Africans all attended church and had their children baptized at Queen Anne's Chapel. The network of relations documented by these baptisms made visible the ways in which ethnic and racial boundaries were made, maintained, and occasionally crossed. The prominence of a Dutch woman as an intercultural go-between, as well as Iroquois women's roles as connectors in the context of baptismal sponsorships suggests that in Iroquoia, women played a role in defining the social borders of their communities in ways elided by the model of male intercultural brokers or Native women's fur trade intermarriages.Sleeper-Smith; Mitchell; Morrissey, "Kaskaskia Social Network." For an examination of the importance of nation, ethnicity, and indigenous political power to Native women's intermarriage, see DuVal. For one case of a female diplomatic broker in eighteenth century Iroquoia, see Parmenter, "Isabel Montour"; and Hirsch. full note Unlike the creation of marital kinship ties as in the Great Lakes and midcontinent, these fictive kinship ties of godparentage within the context of Anglican baptism mirrored Iroquois creation of fictive kinship ties through adoption and diplomatic metaphorsSeeman; Macdougall, 31-32; Fur; Merritt, "Cultural Encounters"; Merritt, At the Crossroads, 51-59 passim. full note on the scale of the household rather than the nation.

The ethnic and national boundaries within the Fort Hunter congregation are most visible in a modularity analysis of the network. Modularity identifies subcommunities within a network which have dense connections within the subcommunity and more sparse connections outside the subcommunity.Because of the small size of this network, modularity was run in Gephi at resolution 2. Weingart, "Networks Demystified"; Newman, "Modularity and Community Structure in Networks." full note In the Fort Hunter network, modularity analysis detected three subcommunities in the Iroquois portion of the network, four subcommunities in the settler portion, and one mixed Native-settler subcommunity which bridged the larger Iroquois and settler portions of the network. The largest division within the congregation as a whole was between the Iroquois and settler portions of the network, bridged only one settler family and a few Iroquois families, but even within those two halves of the congregation, divisions of ethnicity and affinity existed.

| Subcommunity | Canasteje-Oseragighte | Kaghtereni-Uttijagaroondi | Kenderago-Canostens | Bridge | English | Dutch-English | Scots-Irish | Palatine | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Individuals | 163 | 77 | 45 | 60 | 129 | 144 | 60 | 80 | 948 |

| Average degree | 5.9 | 6.3 | 5.2 | 6.2 | 6.7 | 7.3 | 6.7 | 6.1 | 5.9 |

In the settler portion of the congregation, the largest and densest subcommunity was comprised of intermarried English and Dutch congregants. In this subcommunity, individuals had a much higher average degree than individuals in other subcommunities, or in the network as a whole.The median degree for the entire network was 4. The Dutch-English subcommunity average was 7.3 and the median was 5. Degree measures the number of connections an individual has to others, in this case, the number of others they were connected to by a baptism. The density of connections in the Dutch-English subcommunity reflected ethnic differences in the practice of baptismal sponsorship. Historically, Dutch families in New Netherland named very few baptismal sponsors or godparents, reflecting the relatively lower emphasis on godparents as spiritual educators in the Dutch Reformed Church.Tebbenhoff, 567-585; Middleton, "Order and Authority in New Netherland." full note The Fort Hunter register suggests that as these Dutch families intermarried with newer English arrivals, English practices of godparentage became more prevalent.Lynch, Christianizing Kinship; Hanawalt, The Ties that Bound; Moore, "English and Dutch Intermarriages"; Records of the Reformed Dutch Church of New Amsterdam, 1: 10–27. full note Even after the English takeover of New York, seventeenth century Dutch families had previously only named two sponsors, often the child’s grandparents. By the 1730s, children in the Dutch-English subcommunity of the Fort Hunter congregation had as many as two godparents and four baptismal sponsors or witnesses, creating ties between as many as six adults at a time and contributing to the density of connections in this subcommunity. The English subcommunity, which included William Johnson, his common law wife Catherine Weisenberg,O'Toole, 45-47. and other British officers and their wives, had a lower density than the intermarried Dutch-English subcommunity.The distinction between the Dutch-English and English subcommunities is not a firm one and is much less stable than the distinctions between other subcommunities. At many modularities, the Dutch-English and English subcommunities were collapsed into one modularity class, and at other resolutions was fractured into several modularity classes. The other subcommunities discussed here were more firm in their boundaries across different resolutions. The distinction between these two subcommunities reflects distinction between the English affiliated closely with the British colonial infrastructure and those who intermarried with the existing Dutch population.

The density of connections in other subcommunities reflects the extent of their integration with the Dutch-English subcommunities and their assimilation to Anglican baptismal practice. European settlers in New York felt a "protestant responsibility" to offer and accept baptism from other denominations when their own ministers were distant or rarely visited far-flung communities.Lindmark, 7–31. Barclay administered baptism to children of Europeans in the area who did not necessarily consider themselves Anglican even if they attended service and had their children baptized at Fort Hunter. Palatine settlers especially guarded their religious separatism from the Church of England even during their refuge in England before emigration to New York, intermarrying primarily among themselves into the nineteenth century.Otterness, 145; Roeber, 14. The Palatine subcommunity at Fort Hunter had a much lower degree of internal connection than either the Dutch-English or Scots-Irish subcommunities, reflecting both their own baptismal practices of having only a few sponsors, and their separatism from the Dutch-English subcommunities. The Scots-Irish subcommunity, on the other hand, had a more typical degree of internal connections similar to the two bridging communities and the Iroquois subcommunities, but had few connections to the wider network. The baptismal sponsorship practices of the Scots-Irish subcommunity aligned more closely with the Dutch-English subcommunity, and yet only a few individuals connected the two.

The enslaved African community, though comparatively very small in relation to the rest of the network, offers an interesting counterpoint to the connections among and between the Native and white settler subcommunities. Two of the three enslaved natal families, the Powels and the Specks,The Specks remained prominent members of the Albany-area free and enslaved African American community into the present. A project in progress headed by Ian Mumpton at Schuyler Mansion, Albany, traces the family’s roles as baptismal sponsors of other free and enslaved blacks through the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. shared very dense connections to one another. Unlike the Native portion of the congregation, which shared very dense connections between Native people and relatively sparse connections with the settler portion of the congregation, all enslaved people in the Fort Hunter congregaation had ties with both enslaved African and white baptismal sponsors. The enslaved Africans in the Fort Hunter congregation were thoroughly enmeshed in the white settler network despite dense ties between one another, whereas the Iroquois community shared kinship ties with the white community only along its borders. Iroquois communities did have contact with and occasionally adopted African individuals in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, but those ties were made within the context of Iroquois practices rather than Anglican baptism.Hart, "For the Good of Our Souls"; Hart, "Black 'Go-Betweens'", 88-113; Dennis, Cultivating a Landscape of Peace.

The gendered connections between Africans and white sponsors at Fort Hunter underlines the importance of property ownership in sponsoring enslaved children, themselves property. Although the most-connected African individuals were both women, Rachel Speck and Elizabeth Powel, their primary connections were with prominent white men. Speck and Powel lacked documented direct connections with one another in this network, although members of their families sponsored one anothers' children, suggesting that although the two families shared relationships outside the documented baptismal ties. Within the framework of Anglican baptism, however, the white household of residence was a more prominent organizing factor in the creation of baptismal ties. White men were the primary sponsors for enslaved children, both within their own households and in others’. Very few white women sponsored enslaved children, and those who did so were prominent property owners themselves. Mary Phillipse and Anna Clement stood as godparents to enslaved children, at least once each to enslaved children outside of their households. Mary Phillipse was among a small handful of white women who appeared on a Fort Hunter area tax list in the late 1760s, one of the more prominent property holders taxed at seventeen pounds and five day's public work--perhaps done by her slaves.Simms. History of Schoharie County: 150. full note Though not noted in the register or the tax lists as a slave owner, her prominence as a property owner at Fort Hunter suggests that, like white male godparents to enslaved children, Phillipse also owned the parents of children whose baptisms she witnessed. Anna Clement, though less prominent as a property owner, operated a tavern with her husband Joseph. Both white women's roles as godparents to enslaved children despite the broader pattern of white male godparentage to enslaved children suggests that property ownership or ownership of enslaved people was the primary factor white sponsorship of enslaved children.

Liquor Like a Fountain

The Clements were also the primary connectors between the settler and Iroquois portions of the congregation. Anna and Joseph witnessed the Anglican baptisms of four Indian children between 1735 and 1740, including two children of Mohawk interpreter Michael Montour, and the Clement’s children Mary, Elizabeth, John, and Lewis sponsored others.Barclay, "Register of Baptisms." The Clements shared godparentage ties with Sir William Johnson when they witnessed the baptism of the son of Johnson's slaves Powel and Elizabeth in 1738, though the fictive kin tie soured soon after, if it was ever pleasant to begin with. In the early decades of the eighteenth century, Johnson accused Joseph and Anna of selling rum to Indians "so plentifully as if it were water out of a fountain."Preston, 89. Despite a 1748 order from New York Governor George Clinton that the Clements were to cease selling rum to Indians and soldiers and an acrimonious exchange of letters between Johnson and Clement about the ban,George Clinton to Joseph Clement, 1748. SWJP, 1:102-3; Josep Clement to Wyllem Jansen. August 16 1748. SWJP, 1:180. in 1751 the Clements continued to keep a tavern "within twenty yards" of Johnson's house.Preston, 89. It is unclear if the Native families for whom the Clements stood as godparents were also customers at their tavern, but the Clement’s tavern brought them into contact with the many contentious subcommunities at Fort Hunter. Although the Clements, their children and grandchildren were baptized and married in the Dutch Reformed Church at Albany,Records of the Reformed Dutch Church of Albany, 3:12, 114, 123; 4:6, 21, 44, 45, 53, 67, 98. full note the Clements also stood as godparents for the Anglican baptisms of five English children and two enslaved African children between 1738 and 1740. Their eldest son Jacobus, born around the time the Clements began selling rum and seventeen when they stood as godparents for a Native child for the first time, went on to become a trader and interpreter himself,DRCHNY, 7:96; SWJP, 1:625-36; 9:466, 489-90, 518, 926-40, 952-57 suggesting that his family's connections with the Native population were sustained over a long period.

Anna Clement’s prominence as a sponsor at Fort Hunter is suggestive of her wider role in the Fort Hunter community despite William Johnson's views of her. As measured by her betweenness centrality in the network, she was the single most influential individual in the network. Betweenness centrality measures how often an individual is on the shortest path between other individuals in the network,Grandjean, "A Social Network Analysis of Twitter." full note and besides her husband Joseph, Anna Clement was the only person with connections to both the Iroquois and settler portions of the congregation. Herself illiterate and her husband Joseph barely literate, Anna Clement’s position in the Fort Hunter network complicates the picture of the male intercultural mediator. Johnson's papers form part of what might be considered the "canon" of Iroquois studies and especially Iroquois intercultural diplomatic history, and Johnson painted the Clements as alternatively unimportant and subversive. Johnson, who through his self-promotion efforts would become the British Superintendent for Indian Affairs in 1756, and Montour both appear as relatively uninfluential figures in this network as measured by their betweenness centrality. Previous scholarship has suggested that men like Johnson and Montour functioned as intercultural mediators who bridged European and Native spaces.Richter, "Cultural Brokers and Intercultural Politics"; Richter, "Some of Them," 471–84; Richter, Ordeal; Preston; MacLeitch; Countryman, "Toward a Different Iroquois History"; Mandell, "‘Turned Their Minds to Religion’"; Hinderaker, "Translation and Cultural Brokerage." full note In the Fort Hunter network, Anna Clement functioned as Michael Montour’s primary connection to the settler portion of the congregation.On Michael Montour and his family, see Sivertsen, 113-114; Harvey, A History of Wilkes-Barre, 984-985; Hirsch: 81–112; Parmenter, "Isabel Montour," 141–59. full note Although both Montour and Johnson are known from other records to have had diplomatic, economic, familial ties with both the Iroquois and English populations in the Albany area, their connections in the Fort Hunter network suggest that they were relatively unimportant within in the sphere of fictive kinship ties and domsetic interactions. This should be taken both as an indication of this method’s limitations in revealing the totality of interpersonal ties, and as a suggestion that less archivally prominent individuals exerted more influence in different kinds of networks.On archival silencing in traditional and digital history, see Trouillot, Silencing the Past; Kane, "For Wagrassero’s Wife’s Son"; Klein, "The Image of Absence." For an entangled indigenous and settler network which does attempt to reconstruct the totality of all social ties, see Morrissey, "Kaskaskia Social Network" and Morrissey, "Archives of Connection." full note

Tiononderoge

The Iroquois portion of the congregation differed in significant ways from the settler portion of the congregation in the structure of its subcommunities, in the factors that separated its subcommunities, and the structural role of women. The Iroquois portion of the congregation had a lower average density of connections like some subcommunities of the settler portion of the congregation, possibly reflecting a continuity of French Catholic sponsorship practices; Barclay and his predecessors noted that many adults at Tiononderoge were "baptised in Canada."On Catholic practices of godparentage in New France, see Poirier, Religion, Gender, and Kinship in Colonial New France, 175; Sleeper-Smith, 47; Morrissey, "Kaskaskia Social Network," 142. full note Additionally, the network of ties between Iroquois individuals documented in the baptismal register is not complete because it necessarily recorded only religious ties of church members. In 1736, Reverend Barclay wrote to his sponsors, the Society for the Propagation of the Gospel, that only three or four adults at Fort Hunter were unbaptized, though Barclay's continued employment by the SPG was contingent on his conversion and evangelization of the Mohawk.Henry Barclay to the Secretary, August 31, 1736. SPG Letterbooks, Series A, 26:71-72. full note

Like the English and Dutch-English settler subcommunities, the two largest Iroquois subcommunities--the Canostens-Oseragighte and the Kaghtereni-Uttijagaroondi subcommunities--were closely entangled. However, the Iroquois portion of the Fort Hunter congregation had fewer subcommunities, and its subcommunities were divided primarily along clan lines.The Iroquois subcommunities were much more stable than the settler subcommunities across multiple resolutions. Clan identifications were made here using Sivertsen. Although clan and ethnicity are both social constructions of kinship affiliation, Iroquois clans functioned very differently from European nationalities or ethnicities like the Scots-Irish or Palatine divisions of the settler portion of the congregation. Iroquois clans spanned the Six Nations, with clan members from different nations considered kin descended from a common matrilineal female ancestor. Members of the Turtle, Wolf, and Bear clans within the Mohawk nation were related to members of those clans in the Oneida nation.On Iroquois clan structure, see Tooker, "The League of the Iroquois"; Hewitt and Fenton, "The Requickening Address of the Iroquois Condolence Council"; Sivertsen, 12-13. full note

In the Fort Hunter congregation, clans also spanned subcommunities because eighteenth century Iroquois marriages were typically exogamous, meaning that clan members had to marry outside their clan.Hewitt, "A Constitutional League of Peace in the Stone Age of America"; Sivertsen 12-13. full note In 1738, when Thomas Sewatsese and his wife Esther Sewaghaese presented their son Abraham for baptism, the baby was sponsored by Lucas Jughahisese, John Segehowane, and Mary Kakeghtaginhase, recording inter-clan Iroquois ties within the framework of the Anglican church. Thomas was Wolf clan sachem at Tiononderoge, while John was Turtle clan sachem.For Thomas, see Sivertsen 171; for John (or Johannes) see Sivertsen 53 and 124. Lucas, Mary, and Esther’s clan affiliation is unclear. Mary was married to Joseph Sayoenwese, another Turtle clan sachem, meaning she was either Wolf or Bear clan. If she and Esther were sisters, both women were likely Bear clan.Sivertsen, 65. Abraham’s baptism then symbolized the formal Anglican recording of inter-clan ties between prominent members of the three Mohawk clans at Tiononderoge. When Mary and Joseph later sponsored newborn Jacamine, daughter of Bear clan sachem Jonathan Cayenquerago (Kayingwerigoo) and Maria Kajenjkethachtado,Sivertsen, 40, 81, 83-84, 154-157. Sivertsen does not identify the Kayingwerigoo in Barclay's register with Jonathan Cayenquerago, but does note that the name Kajingweriago/Cayenquerago/Swift Arrow was only given to one person at a time, and Jonathan and Maria's other known children were born in the period 1723-1732. they sponsored an infant who was either Turtle or Wolf clan, depending on her mother's lineage. Iroquois sponsors were often, but not always, maternal grandparents of the baptized child,Sivertsen, passim. suggesting that other baptismal sponsors may have been maternal relations as well, and that the practice of Anglican baptism was used to reinforce rather than supplant matrilineal kinship and clan ties.

Because Iroquois baptismal sponsorship often created ties between members of different clans, Iroquois subcommunities were not divided along clan lines. However, certain subcommunities were composed of different alignments of clans, suggesting that members of some Iroquois clans engaged differently with the nearby settler communities. Historians have long argued that internal factionalism caused damage and decline in Iroquois military and political power,Aquila, The Iroquois Restoration, 75-77; Lehman, "The End of the Iroquois Mystique; Richter, "Iroquois versus Iroquois; Richter, "War and Culture"; Richter and Merrell. Beyond the Covenant Chain, 13-14, 26-27, 50-57, 156-159, 173-174; Richter, Ordeal, 6-7, 45-46, 116-117, 175-176, 200-206, 274-275, 307n34; Shannon, Iroquois Diplomacy, 55, 102, 200. For a critique of this approach, see Parmenter, "‘L’Arbre de Paix.’" full note but the alignment of subcommunities within the Fort Hunter congregation does not support this. First, because the Iroquois subcommunities were relatively entangled, especially compared to the fractured settler portion of the congregation. Second, because the alignments of the Iroquois subcommunities, at least as visible at Tiononderoge in the 1730s and 1740s, does not neatly align with the supposedly pro-French and pro-British politics which historians have argued drove Iroquois factionalism. Rather, clan intermarriage and religious denomination were more salient factors in subcommunity formation.

The two Iroquois subcommunities with direct connection to the Bridge community, the Canasteje-Oseragighte and Kaghtereni-Uttijagaroondi subcommunities, were mainly composed of individuals from the Turtle and Bear clans. The Kaghtereni-Uttijagaroondi subcommunity also included a small cluster Wolf clan members, but these were separated by many degrees of connection from the bridge to the settler portion of the congregation. The Kenderago-Canostens subcommunity was most distantly connected to the settler portion of the congregation, and was mainly composed of Wolf and Bear clan members. This may reflect clan engagement with settler communities broadly. William Johnson had a long-standing connection to the Mohawk Turtle clan through Molly and Joseph Brant's stepfather Brant Kanagaradunka,O’Toole, 105, 121-124, 172, 334, Sivertsen, 127-142, 163-171; Leavey, Molly Brant, 23. full note while the most prominent member of the Kenderago-Canostens subcommunity, Abraham Canostens Peterse, once accused William Johnson of disguising a plot in which the French and English conspired to kill all Mohawks. The separation of the Kenderago-Canostens subcommunity may also have been denominational. By 1751, Abraham was a lay preacher and appointed an Anglican Reader, as well as a noted follower of New Light preacher Jonathan Edwards sometimes at odds with the High Anglican aligned Barclay.SWJP, 9:52-54 and 62; DRCHNY, 6:589-590; Sivertsen 144-149. The relative distance of Wolf clan members from the settler portion of the congregation may reflect matrilineal clan approaches to engaging settler communities, religious divisions within the Iroquois community or differences with Barclay, or patterns of clan intermarriage.

Women's clan affiliations in the Fort Hunter network are difficult to determine. Most of the individuals in this network whose clans are known are men, because they appeared more frequently in recorded interactions with Europeans and European recording practices preferentially documented men's biographical details and patrilineages. Many of the women do not appear in other archival records, or appear so rarely that it is difficult to build a concrete picture of their roles in their communities despite what is known of Iroquois women’s roles in governance and matrilineages.Kane, 89-144. Iroquois men additionally appear much more influential than Iroquois women as measured by their betweenness centrality in large part because the calculation of betweenness as measured throughout the network privileges those individuals who had a connection to the narrow bridge between the settler and Iroquois portions of the congregation. By this measure, the most influential individuals in the network were Anna Clement and Esras Teganderasse, occasional preacher and schoolteacher, and son of Canasteje.

As measured by her betweenness, Canasteje herself appears as rather uninfluential in the network, even though she was one of the earliest Iroquois members of the Dutch Reformed Church and sponsored more baptisms than did her son Esras.Sivertsen, 26. As measured by the number of connections to others rather than betweenness, Iroquois women appear much more prominent in the network, on par with men’s prominence. Additionally, if betweenness centrality is calculated separately on the Iroquois and settler portions of the network, Iroquois and settler women appear much more influential internally within their respective portions of the congregation. Although Anna Clement’s prominence as an intercultural connector complicates the story of the male intercultural mediator, an emphasis on intercultural connection nevertheless elides the influence of both Native and settler women within their own communities.

Despite their similarities as measured by internal connections, Iroquois and settler women differed significantly in their structural roles within their portions of the congregation. In the Scots-Irish, Dutch, and Dutch-English subcommunities, connections were mostly heterogeneous, with men and women having balanced numbers of connections with both men and women, while in the Palatine subcommunity, individuals’ connections were more homogeneous with members of their own gender. Connections between all settler subcommunities were also almost all between men; a few settler women like Engeltie Hansen, Mary Quackenbus, and Cornelia Bowen had connections across subcommunities, perhaps as a result of intermarriage, but these were the exception. Iroquois connections across all subcommunities were mainly heterogeneous, but women were the main connectors between subcommunities. Men’s influence as measured by betweenness derived from their role as hubs of subcommunities, while women more often connected subcommunities or otherwise unconnected clusters within subcommunities. Elizabeth Anoghsookte, Elizabeth Teganderasse, and Lydia Kaweghnoke all acted as anchors who connected the Bridge subcommunity to the main body of the Iroquois portion of the congregation, while Jacamine Kaghtereni, Margaret Oseragighte, Canasteje, Christina Brant’s wife, Catherine Kiliane’s wife, Catharine Tewajewasha, Margaret Kinsiago, Margaret Jughahise, Gesina Canostens, Ester Kenderago, and Mary Serehowane all connected the main subcommunities or smaller internal clusters.On Iroquois women's roles in their communities and the importance of matrilineages, see Mann, Iroquoian Women, 165-70; Brown, "Economic Organization and the Position of Women among the Iroquois"; Tooker, "Women in Iroquois Society"; Shoemaker, "The Rise or Fall of Iroquois Women," 303. full note Iroquois men also connected subcommunities, but women much more frequently did so, suggesting that although the network was documented within the framework of Anglican baptismal sponsorship and kinship paradigms, the relationships it recorded reflected Iroquois matrilineal frameworks of kin and community.

And Under One King

As tensions escalated between Britain and France in the years leading to the Seven Years’ War, these divisions between settlers and Iroquois, and Iroquois perceptions of divisions between settler subcommunities, became ever more worrisome to British imperial officials. In late 1756, a Dutch-heritage officer of the New York colonial militia went hunting with an Onondaga acquaintance, a fairly common interaction. The Onondaga man’s knowledge of ethnic tensions within colonial New York proved unsettling enough for the officer to report to William Johnson. "The Indian knowing him to be of Dutch extract, began to speak words reflecting on the English, and told Schuyler [the officer], it would be good that the Albany people or Dutch with the Indians should join and drive the English out of they country. Schuyler says he was surprised to hear the fellow talk in that manner, and turning to him said, we are all one people and under one King."Sir William Johnson to the Earl of Loudon, "Information of an Onondaga Indian Called by the English Corn-Milk." Fort Johnson, March 4, 1757, Huntington Library, Loudon Papers, LO 2971. Colonel Thomas Butler commented darkly in 1757 "if any troubles should arise between the Six Nations and us, it will in great manner or entirely be owing to bad, ignorant people of a different extraction from the English, that makes themselves too buisy telling idle stories. I fear we have too many of those, who speak the indian tongue more or less, and don't consider the consequence of saying, we are Dutch and they are English."Ibid. Several schemes like Eleazar Wheelock’s Indian Charity School popped up in the 1740s and 1750s with hopes of finally converting the Iroquois to British interests,Many accounts of Wheelock’s efforts emphasize his Algonquian alumni, who left a large corpus of their own letters, but the majority of Wheelock’s students were always Iroquois and his funding from the Massachusetts General Assembly was contingent on enrolling Iroquois students. Szasz, "‘Poor Richard Meets the Native American"; Fisher, The Indian Great Awakening; Johnson, To Do Good to My Indian Brethren; Wyss, English Letters and Indian Literacies; Murray, "Pray Sir, Consider a Little"; Hoefnagel, Eleazar Wheelock and the Adventurous Founding of Dartmouth College; Axtell, "Dr. Wheelock and the Iroquois"; Axtell, "Dr. Wheelock’s Little Red School." full note revealing British anxiety that the European residents of New York and the Iroquois were not, in fact, "all one people and under one King."

Social network analysis of the Fort Hunter baptismal network complicates the picture of the male intercultural mediator, and suggests that Iroquois women used Anglican baptism to reinforce inter-clan connections. Even within a single congregation, settler ethnic groups used the practice of baptismal sponsorship to define ethnic community boundaries, while the Iroquois portion of the congregation mediated their contact with the settler community through a sparsely documented Dutch woman, Anna Clement. Clement’s prominence in the fictive kinship context of intercultural baptismal ties suggests that male go-betweens like Michael Montour and William Johnson who are documented through the archive of the diplomatic encounter were not the only intercultural mediators, and in fact may have been relatively uninfluential in the daily contact that produced fictive kinship ties of baptismal sponsorship. Iroquois subcommunities fell along clan rather than ethnic lines, suggesting that even within a single national community like the Mohawk village of Tiononderoge, matrilineal clans approached engagement with settler communities with different goals. Iroquois women acted as bridges between these subcommunities, suggesting that Mohawk and European women as well as men acted as mediators between communities.